Current Project 2021

Free maths resources for ALL students in Key Stage 3 and GCSE

Due the impact of lockdown on students learning Dr Islam has started a project to create free online maths resources for students.

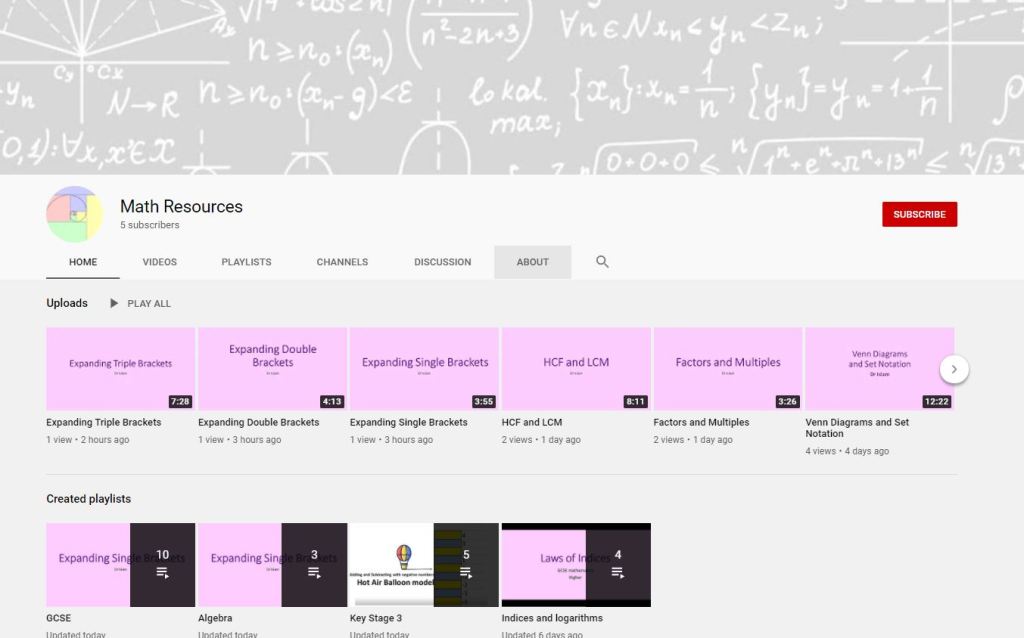

Video lessons on the Youtube channel Math Resource:

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCm-k7_RdG-2SkrWHNQhlrtg

I am Dr Zeenath Ul Islam and I make mathematics videos for educational purposes.

I will try and post regularly to cover most of the curriculum and some maths just for fun too!

Hopefully you will find these useful on your journey as a mathematician!

About Mathematicians for Multiculturalism

Mathematicians for multiculturalism is a mathematical project for mathematicians from all backgrounds. We seek to empower socially disadvantaged students, support mathematicians from minority backgrounds and decolonise the history of the mathematics.

Throughout history, mathematics contributed to the development of civilization (Huckstep, 2000) and it continues to drive technological progress in the age of ‘big data’. Justification for teaching, learning or pursuing any subject falls into two broad categories. Firstly, that the discipline is intrinsically worthwhile, and secondly that it is useful for its application in other fields of life. Thus, in the justification of mathematics education there is a tension between the philosophical study and the practical application of the subject.

Ignorance is not bliss, in fact mathematical ignorance is disempowering and leaves one at the mercy of irrational arguments and empty rhetoric.

From the practical perspective of the student there is a need for the development of basic numeracy and functional mathematical competency in life, such as telling the time or dealing with money (Ward-Penny, 2017). Furthermore, there is the utility of mathematics in work and for the vocational development of the student (Ward-Penny, 2017). It has been argued that highlighting the utility of the subject matter can improve the cognition of the pupil (Huckstep, 2000). Mathematics leads to the development of cognitive techniques which aid the understanding of the world such as pattern spotting, visualization and logic (Ward-Penny, 2017). Mathematics builds a cognitive toolbox vital for critical thinking, personal social development and autonomy (Ward-Penny, 2017). Education can be a tool for social mobility and mathematical education is a way of achieving an electorate with the capacity for logical thinking. Ignorance is not bliss, in fact mathematical ignorance is disempowering and leaves one at the mercy of irrational arguments and empty rhetoric. Finally, mathematics is a “gatekeeper” and can bolster the life choices and broaden the horizons of the student (Ward-Penny, 2017).

Mathematics has many applications across other subjects, however it is taught as a discrete subject because it provides a beautiful and unique way of looking at the world

However, alternative numerical methods to those formally taught in school can be applied to solve ‘real life’ mathematical problems (Carraher, Carraher, & Schliemann, 1985). There is inter-student variation in the utility of school mathematics in daily life, given that it is dependent on an individuals’ own choice to use mathematics (Huckstep, 2000). One may thus argue that mathematics should be taught in conjunction with how it can be used outside of the classroom. It is a popularly held belief that we teach mathematics because of its utility in everyday life (Andrews, 1998; Huckstep, 2000) or as a tool for other disciplines such as data science. However, Andrews (1998) questions the utility of school mathematics and suggests that using utility as a teaching motivation results in students with only an instrumental understanding of the subject. A relational understanding of the subject may be more desirable (Skemp, 2006) but arises when we view mathematics as a unique subject worthy of study in its own right (Andrews, 1998). Mathematics has many applications across other subjects, however it is taught as a discrete subject because it provides a beautiful and unique way of looking at the world (Dreyfus, T & Eisenburgh, T, 1986). Mathematics can be viewed as intrinsically beautiful and may be pursued purely for the intellectual challenge and for the continuance of knowledge to the next generation (Ward-Penny, 2017). In comparison to school mathematics, academic mathematics has a greater emphasis on proof, is subject to revision and can be applied to solve research questions in a wide variety of disciplines such as genetics and genomics (Islam et al., 2013).

A mathematics teacher should inspire the pupils with the subject, explain mathematical concepts clearly and challenge the intellect of their pupils.

In agreement with Ward-Penny (2017) primary school pupils at a state English Primary School believed that they needed to learn mathematics for “jobs”, “everyday life” and were aware that mathematics was a gatekeeper in later life. In agreement with Huckstep (2000) pupils believed mathematics “builds understanding for other things like science. You wouldn’t be able to do science without math.” The utility of mathematics and its application to other fields were also a motivating factor for students at key stage 2, which highlights the link made between cognition and utility by Hucktep (2000). At an English state secondary school pupils were aware of mathematics knowledge being of importance to humanity; if mathematics wasn’t taught “this great knowledge through the ages would be lost from society”. A secondary mathematics teacher highlighted that “mathematics teaches a skill that everybody needs. Sometimes students don’t always realise it but it teaches them problem solving and to be logical.” The pervasiveness of mathematics in society and the utility of mathematics was also appreciated by pupils. Compromises to the teaching ideals of Andrews (1998) were both practical and necessary for lower ability pupils. An instrumental understanding of the topic meant that by the end of the lesson pupils had both the confidence and the tools to answer exam questions successfully. A teacher commented, “students have to master the concepts first, you can’t just start with problem solving. They need the skills to tackle problem solving later on.” The utility of mathematics was never doubted by the pupils; an A-level student stated, “I want to play computer games. You need maths for that.” The utility and importance of learning mathematics was not a myth leaving pupils disillusioned as argued by Andrews (1998), but a reality, as argued by Huckstep (2000), of which they are aware of from as early as key stage 2.

Mathematics was taught in order to equip students with intellectual resilience irrespective of their inclination to appreciate its beauty or their ability. A mathematics teacher should inspire the pupils with the subject, explain mathematical concepts clearly and challenge the intellect of their pupils. Mathematics education can also be viewed as a form of self-knowledge which is of worth to the student (Huckstep, 2000). An empirical view of the world creates order from the chaos of multi-dimensional interconnected systems. Ultimately mathematics, for me, is an answer to the philosophical questions posed by existential nihilism.

References

Andrews, P. (1998). Peddling the myth: Why do we teach mathematics? Mathematics in School, 2(2), 2–4.

Carraher, T. N., Carraher, D. W., & Schliemann, A. D. (1985). Mathematics in the streets and in schools. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 3, 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-835X.1985.tb00951.x

Dreyfus, T, & Eisenburgh, T. (1986). On the aesthetics of mathematical thought. For the Learning of Mathematics, 6(1), 2–10.

Huckstep, P. (2000). The utility of mathematics education: Some response to scepticism. For the Learning of Mathematics, 20(2), 8–13.

Islam, Z. U., Bishop, S. C., Savill, N. J., Rowland, R. R., Lunney, J. K., Trible, B., & Doeschl-Wilson, A. B. (2013). Quantitative analysis of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) viremia profiles from experimental infection: A statistical modelling approach. , Savill, N. J., Rowland, R. R., Lunney, J. K., Trible, B., & Doeschl-Wilson, A. B. (2013). PLoS One, 8(12), e83567. Plos One, 8 (12).

Skemp, R. R. (2006). Relational Understanding and Instrumental Understanding. Mathematics Teaching in the Middle School, 12(2), 88–95.

Ward-Penny, R. (2017). Why do we teach mathematics? In Learning to teach mathematics in secondary school: A companion guide to school experience.